Peripheral Nerve Catheters

While peripheral nerve catheters (PNC’s) may not be a feasible option for many centers, there is no denying their effectiveness. In general, PNC’s can deliver LA far beyond the 12-16 hours routinely offered by single shot blocks. PNC’s have shown similar analgesia in RCT’s when compared to neuraxial anesthesia. Moreover, PNC’s may be feasible in settings where a neuraxial technique is contraindicated, such as coagulopathy or local malignancy.

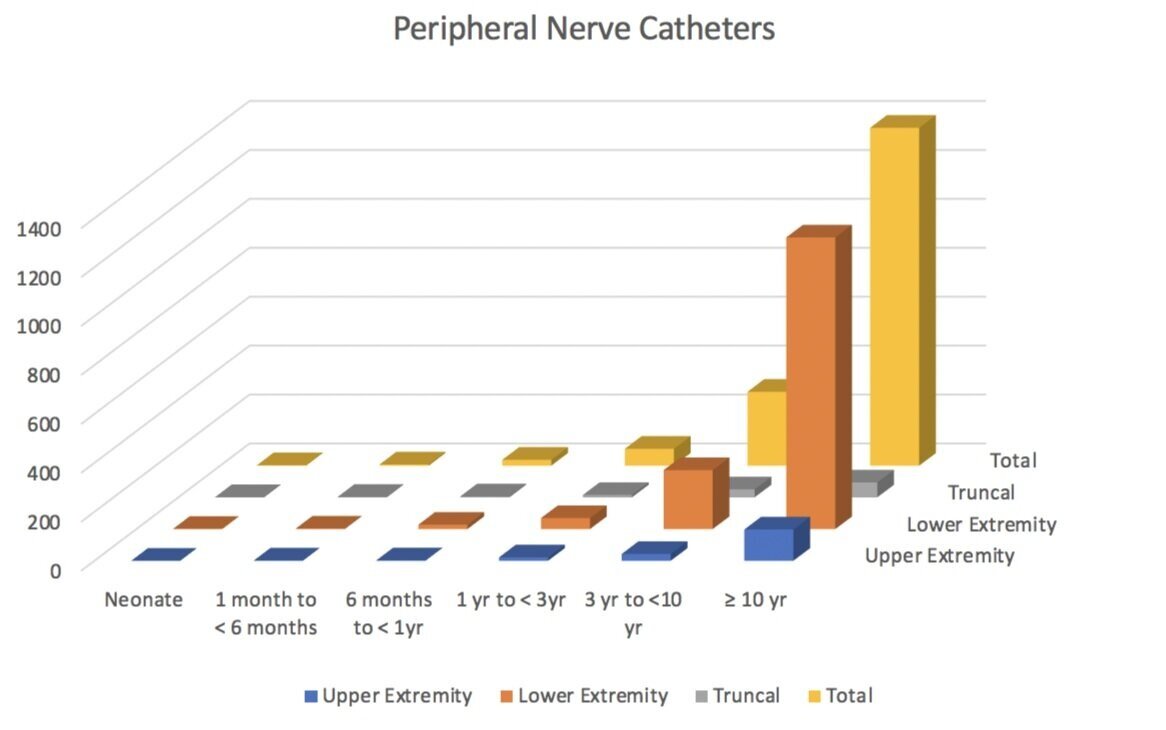

Walker et al, as part of the PRAN consortium, evaluated the safety of PNC’s in children. Looking at over 2,074 PNC’s (mostly in older kids, mostly in the lower extremity), the PRAN researchers found an overall incidence of adverse events (AE) of 12.1%. While this number may seem a little high, they were very conservative in the way they reported complications. Thankfully, most of the complications were minor in nature. There were no reports of persistent neurologic problems, severe infection or LAST, and the researchers estimated the incidence of a serious complication to be around 0.04%. The most common AE’s were catheter malfunction (accidental dislodgement, disconnection and leakage), vascular puncture, and superficial infections. Similar to other studies, they found that patients with PNC’s for greater than 3 days were at increased risk. All reported infections were minor and superficial, and no deep tissue infection, abscess, or sepsis was reported.

Adapted from “Walker, B.J., Long, J.B., De Oliveira, G.S., Szmuk, P., Setiawan, C., Polaner, D.M. and Suresh, S., 2015. Peripheral nerve catheters in children: an analysis of safety and practice patterns from the pediatric regional anesthesia network (PRAN). British journal of anaesthesia, 115(3), pp.457-462.”

Nicoletti et al also performed a literature review looking at the risk of colonization of PNC ‘s. The risk of bacterial colonization has been suggested to be between 6-57%, though when catheters were removed sterilely the incidence of colonization was found to be as low as 6%, implying contamination during routine removal. Inflammation was estimated to be between 3-9%, and it’s been suggested that it may relate to catheter movements and local irritation of the subcutaneous tissue. The incidence of actual infection was estimated to be < 1%. Pathogen penetration is thought to be the major player responsible for PNC infections via contamination of hubs, filters, etc. Chlorhexidine cleaning solutions appear to be superior to iodine solutions, while Chlorhexidine-impregnated dressings offered no discernible benefit. Similar to Walker et al, they also found that the single greatest risk factor for infection is the duration of catheter use.

One additional aspect the researchers evaluated was the use of catheter tunneling. Tunneling has the potential advantage of decreasing catheter migration (internally or externally), and perhaps reducing catheter colonization and infection. While definitive evidence is still lacking, overall, Nicoletti et al found that tunneling seems to be related to lower dislodgement, colonization and infection rates. With children seemingly more likely to sweat or wiggle around in bed, as well as being more likely to pull at visible (and reachable) catheters, tunneling may offer a distinct advantage in our patient population.

Peripheral Nerve Catheter Technique

Multiple techniques have been described, with variations for creating the tunnel, strategies to prevent dislodgement (single vs double-tunnel vs looping), ways to reduce potential needle stick injuries, and methods of threading the catheter to improve ease and functional catheter success. Rather than just integrate one or two techniques, adding many or most of these to your personal technique may have an outsized effect on your success rate. As Darren Hardy, author of The Compound Effect, is wont to say, “small choices + consistency + time = significant results.” For a wonderful examination of this in the context of placing PNC’s in children, Maria et al wrote an article highlighting the difficulties they encountered, the solutions they came up with, as well as measuring the impact of integrating all of these techniques had on their catheter success rate. The main issues they encountered in placing PNC’s were locating the catheter tip, introducing the catheter, the length of catheter to be introduced, and catheter fixation. Much of what is described below is taken directly from this article.

Lastly, as this is an indwelling device, full sterile precautions (gloves, gown, mask, sterile prep and drapes) should be followed when placing a PNC.

Set-up—while there are PNC kits, depending on the patient’s age, desired catheter location, and available resources, a standard epidural kit may also suffice. This is what we typically use, though if the child is young and the desired catheter location shallow, we may substitute a similar gauge, though smaller length epidural needle for ease of use.

Flushing the epidural needle before entering the skin

Accidentally introducing and injecting air while using ultrasound guidance may interfere with the image quality and the ability to adequately visualize relevant structures, so please remember to flush prior to entering the skin.

Rather than initially attaching a syringe to the epidural for flushing and hydrodissection, Maria et al advanced an epidural catheter with a syringe attached into the epidural needle so that the catheter tip was just inside the end of the needle. They then flushed the needle/catheter unit prior to starting the procedure.

Not only does this eliminate the need for disconnecting your flush/hydrodissection setup after you’ve correctly identified the target site, but with the catheter already threaded and positioned at the epidural needle tip, locating the catheter tip on ultrasound should be much simpler.

One small tip is that when injecting, make sure to have the catheter threading assist guide firmly connected to the epidural hub. When injecting through the catheter, rather than forging a path subcutaneously, the solution may choose to take the easier route, out the other end of the touhy! Having the adapter firmly attached will reduce the likelihood of retrograde injection out the back of the needle.

Advancing the needle under direct ultrasound guidance in the long axis

This allows one to visualize the needle tip throughout the entire process, and, by extension, the catheter tip once you are ready to advance it (since it is already threaded to the mouth of the epidural needle).

Introducing the catheter using a two-person technique

Once you’ve identified the correct plane and are ready to advance the catheter, having a second person to help will increase your chances of success. There are two options:

1) Hand off the ultrasound probe to the second set of hands, while you hold the epidural needle and thread the catheter (Maria et al technique)

2) Keep things the way that they are to potentially reduce needle movement. The second person (who presumably has been hydrodissecting at your discretion) advances the catheter, while you continue to hold the probe and needle throughout the process. I prefer this technique, as it allows me to still manipulate the needle and probe simultaneously if I need to make minor adjustments. If you advance the needle like your holding a pencil, with the heel of you hand resting on the patient, your hand will already be underneath the epidural hub, and will allow easy access for catheter advancement.

The length of catheter to be advanced

Under direct visualization, thread the catheter out of the epidural needle into the desired location. Withdrawing slightly and/or rotating the needle may help if you encounter difficulty threading.

While we typically thread epidural catheters at least 4 cm into the epidural space, that may not be feasible for some PNC’s. Rather than try and force the catheter into the space, Maria et al recommends advancing the catheter until one meets resistance or you have advanced at least 5 cm. Advancing beyond 5 cm has been associated with catheter entrapment.

Catheter fixation

There a multitude of described tunneling techniques. Choose whichever makes the most sense to you. We typically create a tunnel by advancing and 18g angiocatheter from an adjacent area towards the initial epidural catheter exit site. You should carefully advance the needle until it emerges in the same exit hole as the epidural catheter, using a needle cap to protect the exiting needle tip from injuring either the operator or the adjacent epidural catheter. Once you’ve emerged at the catheter exit site, remove the needle while leaving the angiocatheter in place. Carefully advance the epidural catheter retrograde through angiocatheter. Once the catheter has been threaded, carefully remove the angiocatheter being mindful not to withdraw the catheter itself. After the angoicatheter has been removed, slowly withdraw any remaining slack on the catheter until the catheter is fully inside the tunnel, being careful not to leave a skin bridge (any gap at the original epidural placement site).

With the catheter effectively tunneled, place some dermabond at the original epidural puncture site, as well as at the tunneled end. This may further reduce catheter migration and potential for leakage around the catheter. Maria et al also recommend dermabonding a short segment of the epidural catheter (1-2cm) to allow for easy recognition of catheter depth during daily rounds. In addition, we then place mastisol adjacent to the catheter, then coil a small segment before placing steri-strips on top of the coil.

A transparent dressing should be placed allowing for easy daily inspection. This dressing should only be changed if medically necessary, as any dressing change may lead to catheter dislodgement and the potential for catheter colonization and infection.

Catheter removal

Once the LA infusion has been stopped and patients have been transitioned to an effective alternative analgesic regimen, the catheter can be removed.

If one encounters difficulty in removing the catheter, flushing the catheter, or even infusing high-volume sterile solutions may loosen the catheter, and thus allow removal.

Severe pain on catheter removal should be approached with caution. Further workup, including imaging, may be necessary. Interventional radiology or surgical intervention should be considered.

Boezaart, A.P. and Warltier, D.C., 2006. Perineural infusion of local anesthetics. The Journal of the American Society of Anesthesiologists, 104(4), pp.872-880.

Bösenberg, A.T., Bland, B.A., Schulte-Steinberg, O. and Downing, J.W., 1988. Thoracic epidural anesthesia via caudal route in infants. The Journal of the American Society of Anesthesiologists, 69(2), pp.265-268.

Kumar, N. and Chambers, W.A. (2000), Tunnelling epidural catheters: a worthwhile exercise?. Anaesthesia, 55: 625-626

Moran, K.T., McEntee, G., Jones, B., Hone, R., Duignan, J.P. and O'malley, E., 1987. To tunnel or not to tunnel catheters for parenteral nutrition. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England, 69(5), p.235.

Walker, B.J., Long, J.B., De Oliveira, G.S., Szmuk, P., Setiawan, C., Polaner, D.M. and Suresh, S., 2015. Peripheral nerve catheters in children: an analysis of safety and practice patterns from the pediatric regional anesthesia network (PRAN). British journal of anaesthesia, 115(3), pp.457-462.

Nicolotti, D., Iotti, E., Fanelli, G. and Compagnone, C., 2016. Perineural catheter infection: a systematic review of the literature. Journal of clinical anesthesia, 35, pp.123-128.

Tsui, B.C., Wagner, A., Cave, D. and Kearney, R., 2004. Thoracic and lumbar epidural analgesia via the caudal approach using electrical stimulation guidance in pediatric patients: a review of 289 patients. The Journal of the American Society of Anesthesiologists, 100(3), pp.683-689.

Sethna, N.F., Clendenin, D., Athiraman, U., Solodiuk, J., Rodriguez, D.P., Zurakowski, D. and Warner, D.S., 2010. Incidence of epidural catheter-associated infections after continuous epidural analgesia in children. The Journal of the American Society of Anesthesiologists, 113(1), pp.224-232.

Tripathi, M., 2012. Safe practices in epidural catheter tunneling. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol, 28, pp.138-9.

Lin, C., Reece-Nguyen, T. and Tsui, B.C., 2020. A retrograde tunnelling technique for regional anesthesia catheters: how to avoid the skin bridge. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d'anesthésie, 67(4), pp.489-490.

Sakai, W., Tachibana, S., Chaki, T., Nakazato, N., Horiguchi, Y., Nawa, Y. and Yamakage, M., 2021. Safety of an improved pediatric epidural tunneling technique for catheter shear. Pediatric Anesthesia.

Tripathi, M. and Pandey, M., 2000. Epidural catheter fixation: subcutaneous tunnelling with a loop to prevent displacement. Anaesthesia, 55(11), pp.1113-1116.

Burstal, R., Wegener, F., Hayes, C. and Lantry, G., 1998. Subcutaneous tunnelling of epidural catheters for postoperative analgesia to prevent accidental dislodgement: a randomized controlled trial. Anaesthesia and intensive care, 26(2), pp.147-151.

Byrne, K.P.A. and Freeman, V.Y., 2014. Force of removal for untunnelled, tunnelled and double‐tunnelled peripheral nerve catheters. Anaesthesia, 69(3), pp.245-248.

De José María, B., Banús, E., Navarro‐Egea, M. and Banchs, R.J., 2011. Tips and tricks to facilitate ultrasound‐guided placement of peripheral nerve catheters in children. Pediatric Anesthesia, 21(9), pp.974-979.

Goel, D., Yadav, B., Lewis, P., Sharma, K. and Vellody, R., 2017. Tunneled catheter placement in a pediatric patient: a novel approach. Journal of the Association for Vascular Access, 22(4), pp.205-209.

Offerdahl MR, Lennon RL, Horlocker TT. Successful removal of a knotted fascia iliaca catheter: principles of patient positioning for peripheral nerve catheter extraction. Anesth Analg 2004; 99: 1550-2.

Motamed C, Bouaziz H, Mercier FJ, Benhamou D. Knotting of a femoral catheter. Reg Anesth 1997; 22: 486-7.

Clendenen, S.R., Robards, C.B., Greengrass, R.A. and Brull, S.J., 2011. Complications of peripheral nerve catheter removal at home: case series of five ambulatory interscalene blocks. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d'anesthésie, 58(1), pp.62-67.

Brenier, G., Salces, A., Maguès, J.P. and Fuzier, R., 2010. Peripheral nerve catheter entrapment is not always related to knotting. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d'anesthésie, 57(2), pp.183-184.

Despond, O. and Kohut, G.N., 2010. Broken interscalene brachial plexus catheter: surgical removal or not?. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 110(2), pp.643-644.