Femoral Nerve Block

Indications: Surgery of the femur below the hip (osteotomies, fracture repair, epiphysiodesis), anterior knee surgery (arthroscopy, ACL reconstruction, MPFL reconstruction), procedures involving the superficial medial malleolus; Vastus lateralis/medialis muscle biopsies.

Technique: Probe- Linear; Needle- In-plane

The child is placed supine with the leg slightly abducted. External hip rotation (“frog-leg” position) may be of use for obese patients.

A linear ultrasound probe of corresponding size to the pediatric patient is placed in the inguinal crease, just below the inguinal ligament. The femoral artery is an easily identifiable target to begin with. Often the probe must be tilted or moved cephalad to enable visualization of a single pulsatile artery, prior to its split due to the takeoff of the deep femoral (profunda femoris) artery. Care must also be maintained to not move so cephalad that one is above the inguinal ligament, formed between the ASIS and pubic tubercle, as this may lead to an intraperitoneal injection.

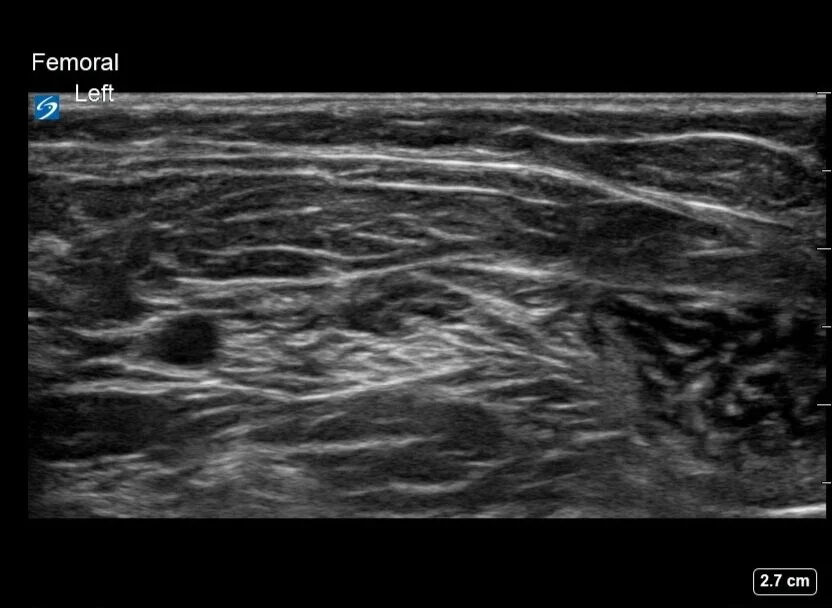

The femoral nerve may be identified as a hyperechoic structure just lateral to the femoral artery. In the ideal case, it can be seen immediately lateral to the femoral artery, as a bright “cluster of grapes”. Realistically, especially in our smallest of patients, its shape may be triangular, oblong, or very flat, and may lie more lateral than is classically seen in ideal adult patient examples.

The needle is advanced from lateral to medial, with the target being just above or below the femoral nerve. Injection at a single location often provides circumferential spread. At times, redirection to the opposite side of the nerve, to allow for local anesthetic deposition surrounding the nerve, is needed.

If ultrasound visualization is challenging, femoral nerve confirmation can be obtained with the addition of nerve stimulation eliciting patellar snap. If sartorius contraction occurs, the needle should be directed more laterally and slightly deeper. Eliciting nerve stimulation at 0.3-0.5mA is required during stimulator-only-based block techniques, but when combining it with ultrasound and using it simply for identification of nerve tissue, stimulator response at a higher amperage is acceptable.

Another tip is to keep the probe perpendicular to the long axis of the leg, find the femoral artery bifurcation and then trace the artery back proximally 1-2cm. Now identify the iliopsoas muscle. The femoral nerve lies on top of the iliopsoas muscle, and the sartorius muscle should overlay the lateral half of the iliopsoas muscle (thanks to Dr. Peter Merjavy and Dr. Robbie Erskine for the tips!)

A continuous catheter can be utilized, and is most commonly placed via the same lateral-to-medial needle approach as the single-shot block. A more lateral starting skin puncture location is recommended as it may help stabilize this otherwise superficial catheter. Placement near the nerve with the confirmation of local spread via the catheter under the fascia iliaca is required.

Dose: 0.5 - 1.5mg/kg of Bupivacaine or Ropivacaine (roughly 0.2 - 0.3mL/kg).

Coverage: Anterior thigh, anteromedial knee, and anteromedial lower leg to the level of the medial malleolus.

The lateral thigh requires separate lateral femoral cutaneous coverage. A fascia iliaca block may be required if blockade of both the femoral and lateral femoral cutaneous nerves is desired. A small space on the medial thigh, just above the knee, requires obturator nerve coverage.

Motor function to the quadriceps muscle group will be affected. If a sensory block to the knee or below, without motor involvement, is required an adductor canal block or more distal saphenous nerve block can be utilized.

Potential Complications: Rare in this straightforward, superficial block, and consistent with the complications of all peripheral nerve blocks including: bleeding, infection, intraneural injection and LAST.

Patient Positioning and Probe Orientation

Expected Coverage

Ultrasound Images

Femoral nerve block is one of the most commonly performed blocks in children due to its ease of placement, high success rate, and broad indication for use (Flack and Anderson). The technique was first described in 1979 by Grossbrad and Love. Adding ultrasound guidance was later reviewed by Marhofer et al. in 1997. Oberndoefer et al. showed that it added increased duration of analgesia and the ability to use smaller local anesthetic volumes when compared to nerve stimulation techniques.

Femoral nerve blocks have been shown to improve outcomes (length of stay, analgesia, and admission rates) in pediatric knee arthroscopy surgeries in particular (Schloss et al.). For local anesthetic choice in this population, Veneziano et al. noted 0.5% ropivacaine offered superior analgesia as compared to 0.2% ropivacaine and 0.25% bupivacaine, using 0.26-0.29mL/kg mean volumes. In anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, one must consider a nerve block’s contribution to persistent functional deficits, such as prolonged quadriceps weakness. Single-injection femoral nerve blocks cause less deficit than femoral nerve catheters (Parikh et al.). In this patient population, where functionality for the rapid return to sports is extremely important, one may consider completely avoiding the motor inhibition a femoral nerve block provides by placing an adductor canal block instead.

Its application reaches beyond orthopedic femur and knee surgery. General anesthesia for children with myopathies such as mitochondrial, central core, and King Denborough, can be especially challenging. A provider may need to minimize or even avoid particular IV anesthetics or inhaled gases, depending on the type of myopathy. Often the reason for a biopsy is an undiagnosed myopathy, and it is unclear what the appropriate anesthetic agent choice should be. A dense femoral nerve block (for example 0.5% bupivacaine 0.25ml/kg) (Sethuraman, Neema, and Rathod) combined with sedation offers the ability to expose these fragile patients to very little of our potentially triggering traditional anesthetic agents.

Flack S, Anderson C. Ultrasound guided lower extremity blocks. Paediatr Anaesth. 2012;22(1):72-80.

Grossbard GD, Love BR. Femoral nerve block: a simple and safe method of instant analgesia for femoral shaft fractures in children. Aust N Z J Surg. 1979;49(5):592-594.

Marhofer P, Schrögendorfer K, Koinig H, Kapral S, Weinstabl C, Mayer N. Ultrasonographic guidance improves sensory block and onset time of three-in-one blocks. Anesth Analg. 1997;85(4):854-857.

Oberndorfer U, Marhofer P, Bösenberg A, et al. Ultrasonographic guidance for sciatic and femoral nerve blocks in children. Br J Anaesth. 2007;98(6):797-801.

Schloss B, Bhalla T, Klingele K, Phillips D, Prestwich B, Tobias JD. A retrospective review of femoral nerve block for postoperative analgesia after knee surgery in the pediatric population. J Pediatr Orthop. 2014;34(4):459-461.

Veneziano G, Tripi J, Tumin D, et al. Femoral nerve blockade using various concentrations of local anesthetic for knee arthroscopy in the pediatric population. J Pain Res. 2016;9:1073-1079.

Parikh HB, Gagliardi AG, Howell DR, Albright JC, Mandler TN. Femoral nerve catheters and limb strength asymmetry at 6 months after primary anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in pediatric patients. Polaner D, ed. Pediatr Anaesth. 2020;30(10):1109-1115.

Sethuraman M, Neema PK, Rathod RC. Combined monitored anesthesia care and femoral nerve block for muscle biopsy in children with myopathies. Paediatr Anaesth. 2008;18(7):691.