Surgical Buy-In

When I first graduated fellowship and was trying to figure out how to best actualize my vision of how I wanted to practice, it became readily apparent that surgical buy-in for any potential change to current culture was going to be a significant barrier to entry. While I might be able to convince a surgeon on Monday to let me do a rectus sheath block for the lap appy, next week I was paired with an entirely different surgeon who never saw how well the kid last week did. It was always an uphill battle. Factor in that our practice had over 30 pediatric anesthesiologists and 7 pediatric surgeons, and the likelihood that I would be able to single-handedly change the surgical mentality was slim to none. I would need more like-minded people if this vision was ever going to achieve liftoff. Thankfully, our group was in the midst of a pediatric anesthesiologist hiring spree. Before I knew it a crop of young, talented, pediatric anesthesiologists with an interest in regional anesthesia materialized. With the core nucleus of Natalie Barnett, Brian Nicholas, Benita Liao, Michelle Kars, Tanya Challah, Tripali Kundu, Michael Pettei, Teddy Barkulis and myself, we reached critical mass and set out to shake things up.

I shared my vision with them about how I thought we should be practicing, as well as my battle plan for getting surgical buy-in.

One surgery. One block. One surgeon.

It became our mantra. Consistency is the key to success.

One surgery. Pick a procedure that is commonly performed. For us, the most common surgical procedure performed was a laparoscopic appendectomy, with our institution averaging over 600 a year. Though there were always exceptions to the rule, our surgeons typically performed the bulk of these procedures laparoscopically through a single umbilical incision. With roughly 10-12 of these done weekly, this seemed like the best choice.

One block. We wanted something that would reliably supply dense peri-umbilical coverage. Ideally, it would be quick to perform, would have a low risk of adverse events, and would be easy to for others to learn. To me, it seemed obvious—a rectus sheath block. The sonoanatomy is readily and easily identifiable. With no critical structures directly in the needle path, we wouldn’t have as much to be worried about while training others. Because it is anteriorly located, we could keep patients supine. While surgeons typically don’t scoff at letting junior staff or medical students meticulously (and most times tediously) close skin, the thought of adding any non-surgical time to the procedure can easily turn into a confrontation. By choosing a quick, low-risk, technically easy block that didn‘t require a position change, it was less of a tug of war come block time.

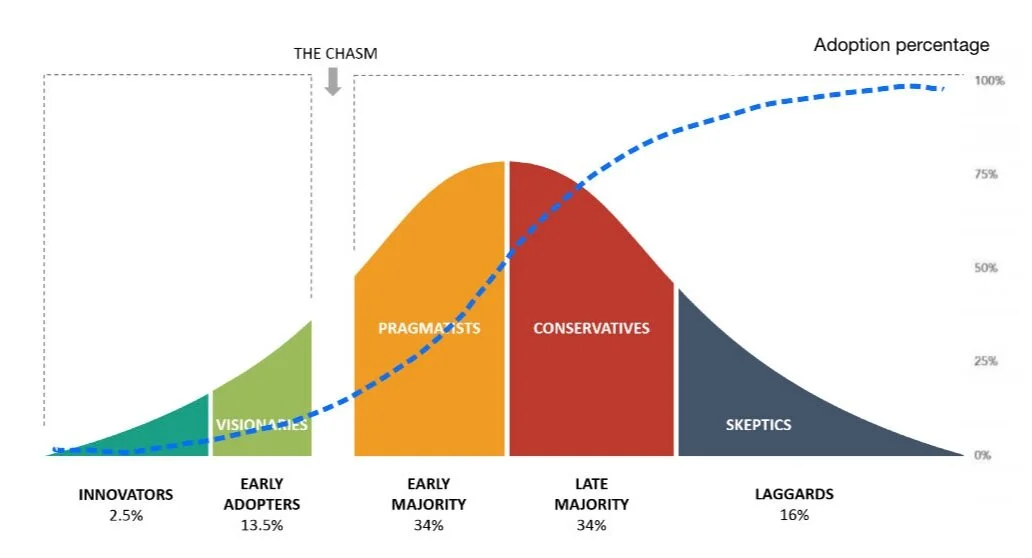

One surgeon. One of the biggest challenges for adopting change is “the chasm” that typically exists between early adopters and the more pragmatic majority.

Innovation Adoption Lifecycle

The ‘Diffusion of Innovation’ is a theory that seeks to explain how, why, and at what rate new ideas and technology spread. The superimposed S-shaped curve shows the rate of adoption. The “chasm” is the gap that exists between early visionaries and enthusiasts, and adoption by the much larger majority. This chasm is something all enthusiasts and early adopters must cross.

We knew that in order for us to gain real acceptance for regional techniques, we needed surgical buy-in. We also knew we needed to be strategic about how we rolled this out, which surgeons to approach. We were not going to waste our energy (and perhaps our only opportunity) trying to convince the skeptical or conservative “old school” surgeons the benefits of regional anesthesia. We decided to segment our market. For us, the low-hanging fruit were the surgeons who didn’t mind us spending a few extra minutes doing a block, either because they respected what we were trying to do, or they were never in the rooms on time anyway.

Everett Rogers, the author of Diffusion of Innovations, proposes that four main elements influence the spread of a new idea: the innovation itself, communication channels, time, and a social system. This process relies heavily on human capital to help spread the gospel. The innovation must be widely adopted in order to self-sustain. Within the rate of adoption, there is a point at which an innovation reaches critical mass.

For the next few weeks, we made sure every child having a single incision lap appy got a pre-incision rectus sheath block. If the staff anesthesiologist didn’t know how to perform the block, one of us who did would make ourselves available to teach them. By the end of each week, the surgeon staffing the peds emergency OR was convinced. More importantly, the surgical house staff and PACU nurses were also convinced. When the next surgeon would rotate on service, the residents, fellows and nurses became our greatest advocates, as these people typically spent considerably more time with these children post-op. Most children received no narcotics intraoperatively, and many of them required no narcotics throughout their entire peri-op course. Over time, even the most skeptical surgeons were won over, not so much by us, but by everyone else touting how much better these kids looked. We had reached critical mass. After that, introducing other blocks for specific surgical procedures became a much easier conversation.

Moral of the story: Find your early adopters and early majority. Start small. Be strategic. Be consistent. Be patient.